Teerk Roo Ra

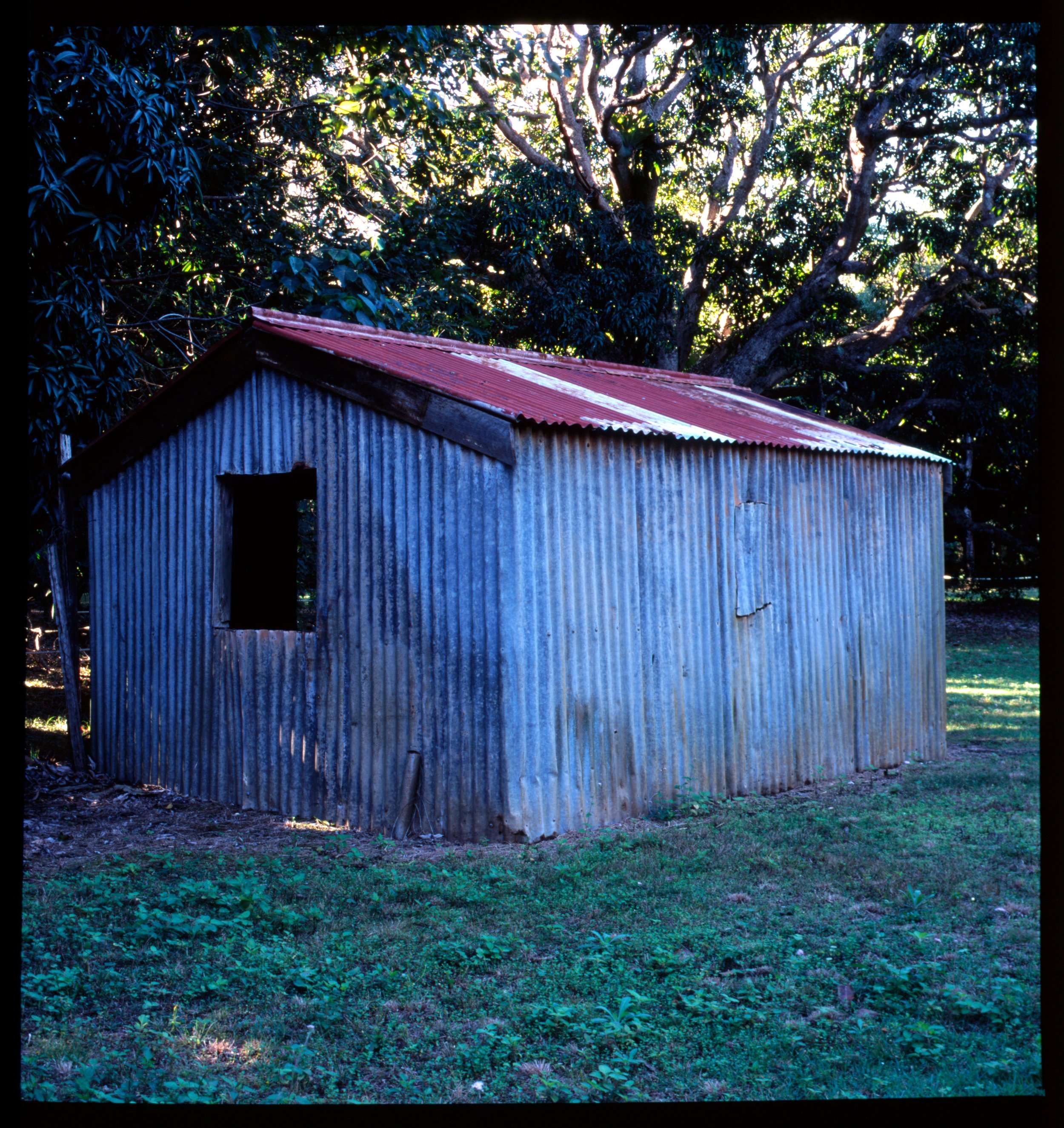

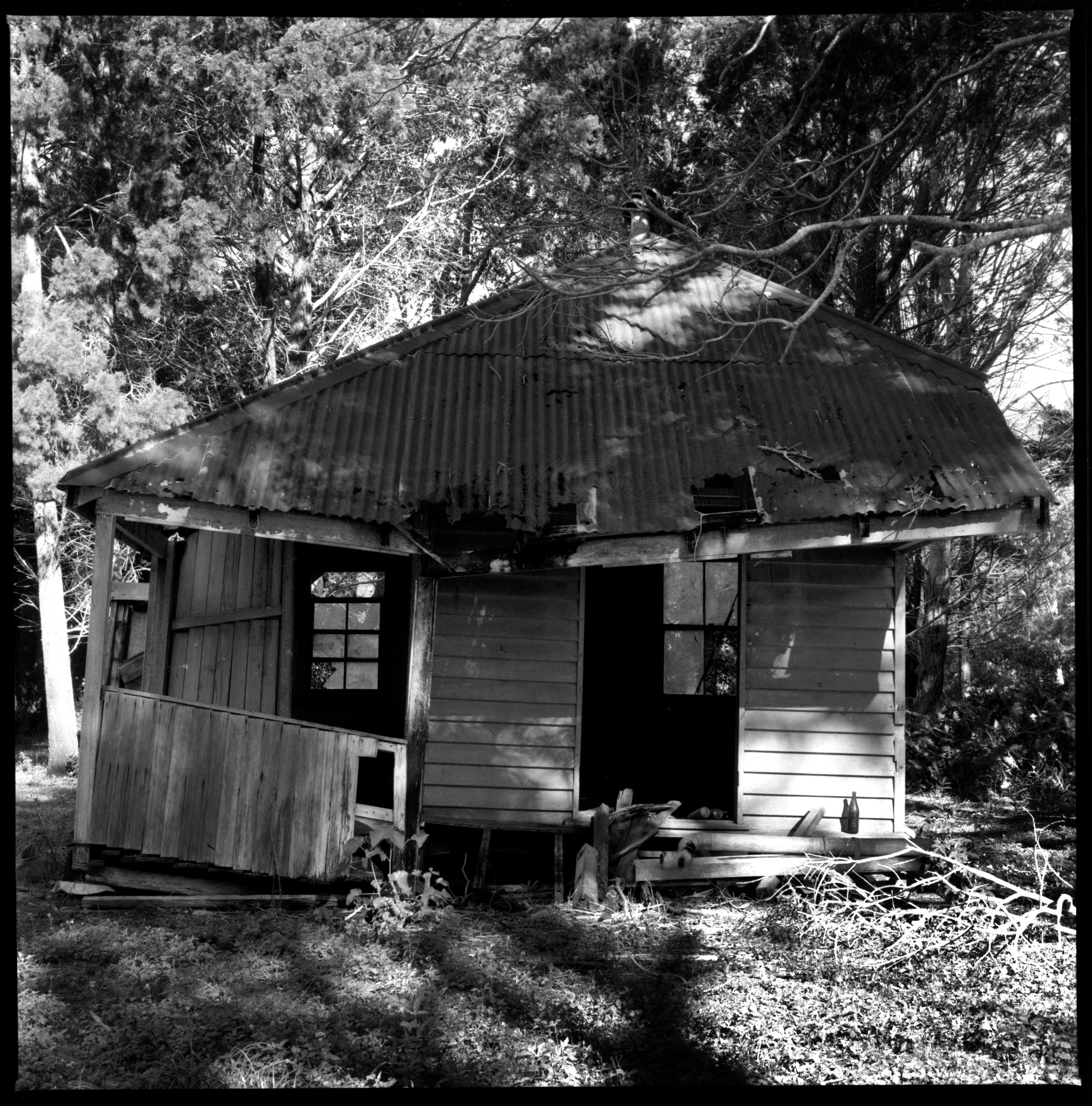

Peel Island Lazaret ResidencyFridge, UltraChrome on Ilford Smooth Pearl, 61x61 cm, 2008

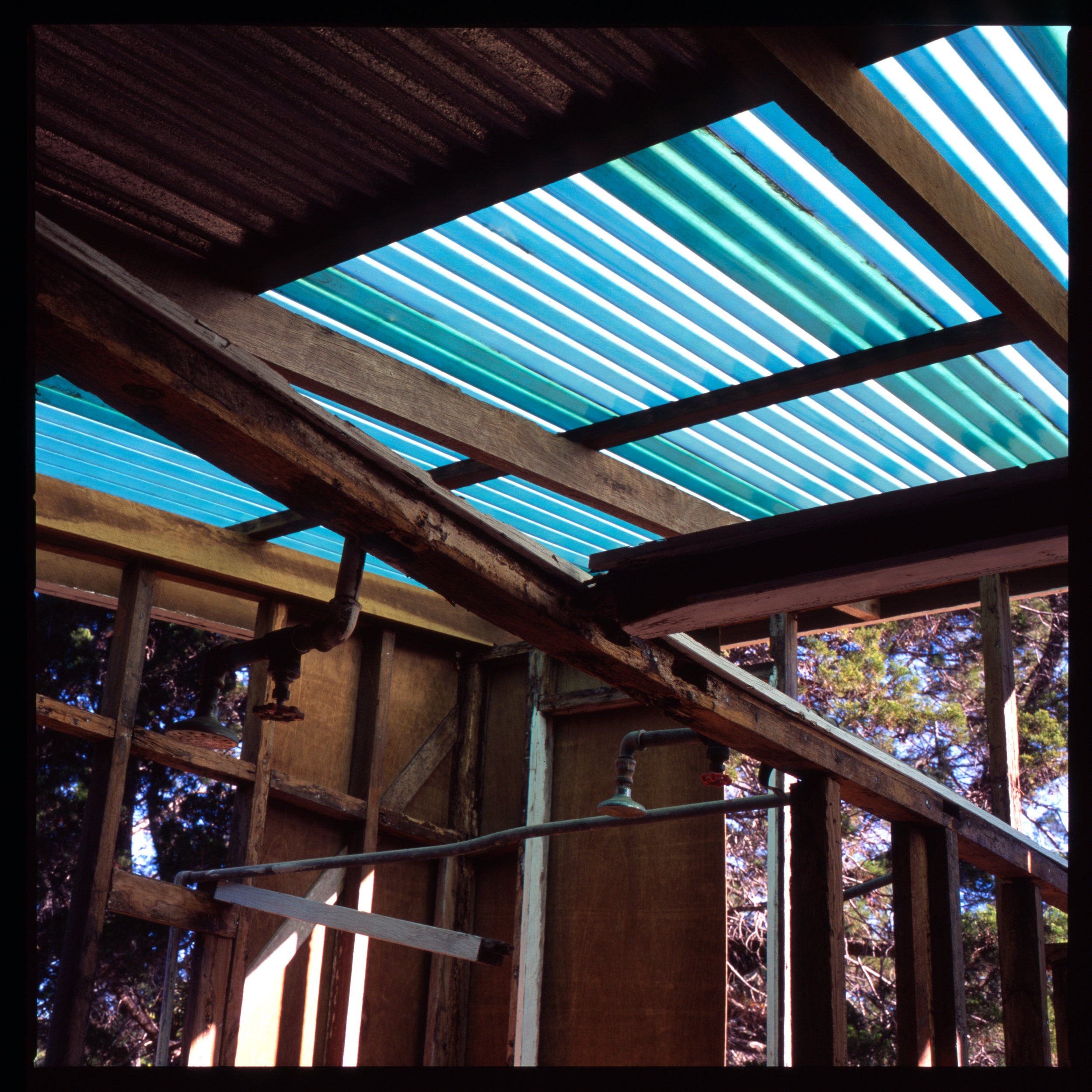

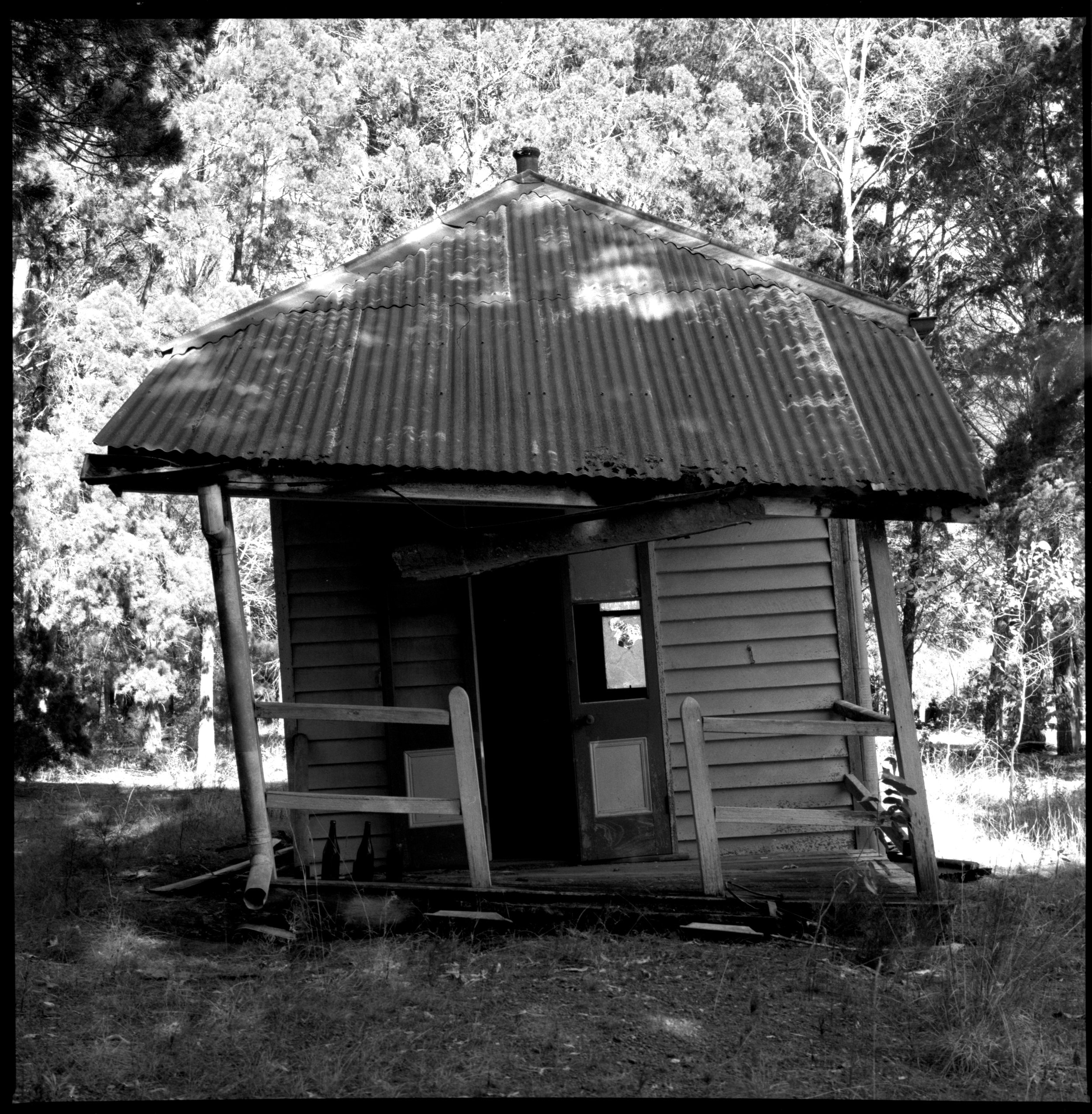

Veranda, UltraChrome on Ilford Smooth Pearl, 61x61 cm, 2008

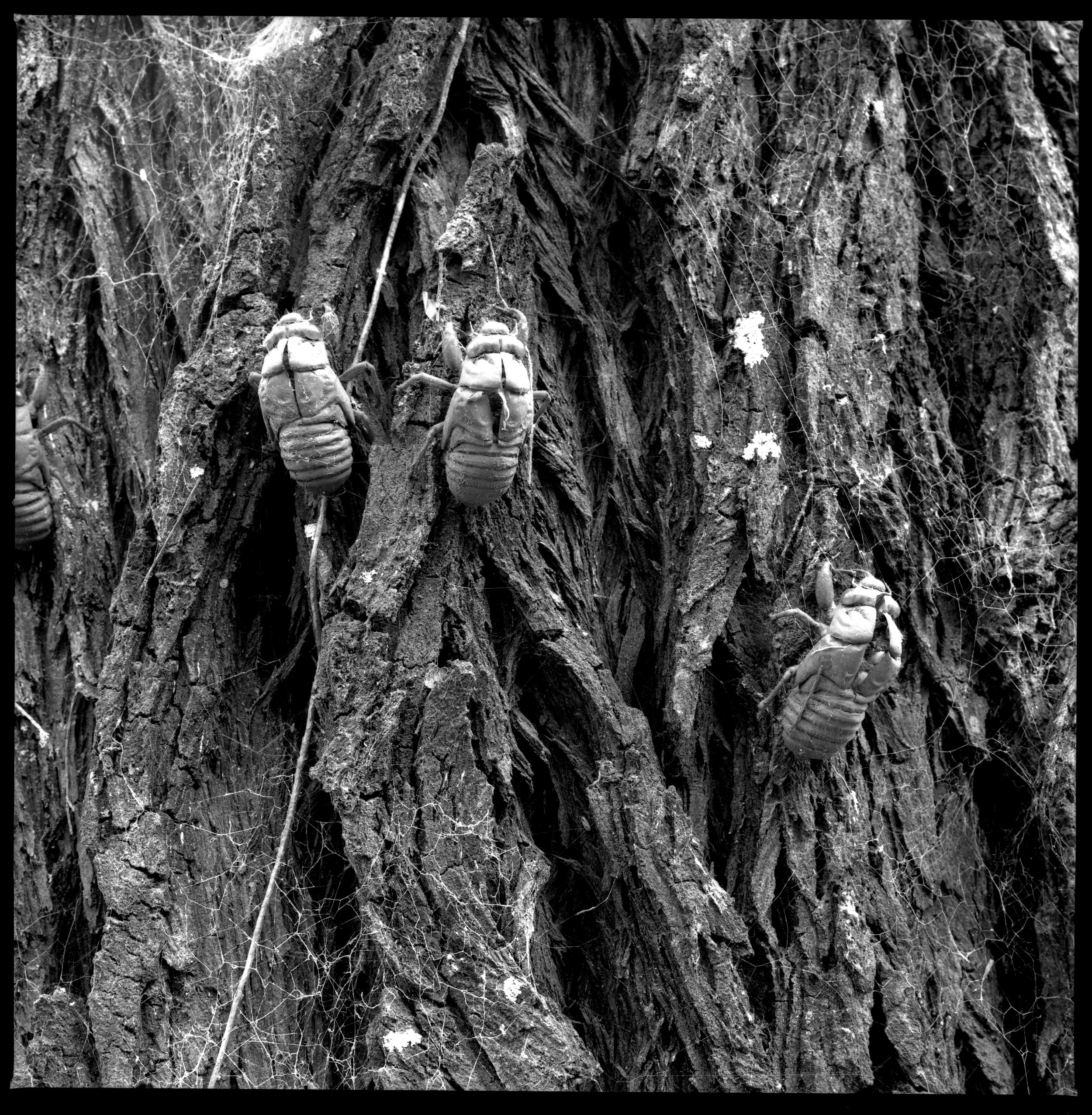

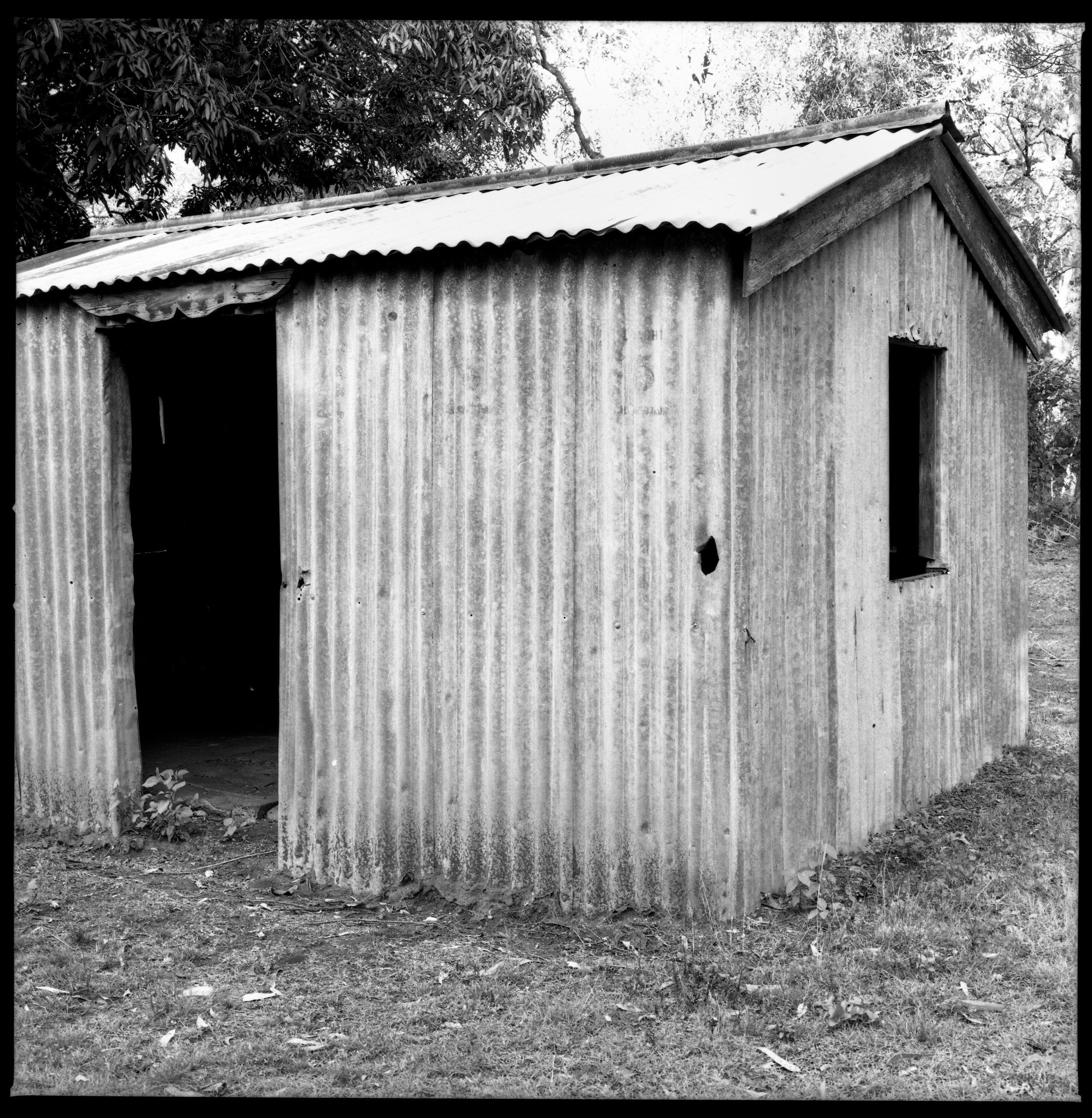

The Gums, UltraChrome on Ilford Smooth Pearl, 61x61 cm, 2008

I acknowledge the Quandamooka Yoolloobarrabee people as the Traditional Custodians and knowledge-holders of the unceded Teerk Roo Ra lands of on which I lived, learned and worked. I acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first artists and storytellers on the Australian continent. I pay my respects to Elders past, present and future. More on the Peel Island Lazaret here.

Moe Louanjli’s art practice has utilised a number of media. He is interested in different ways of mapping, and also in the way in which dreams of utopia can affect such undertakings as urban planning. So, the lazaret was interesting as a kind of dystopian model. During his time there Moe produced a large number of photographic images, each of which bear traces of the ways in which the inhabitants of the island interacted with the environment. Several material aspects of life on the island emerge as important to this documentation.

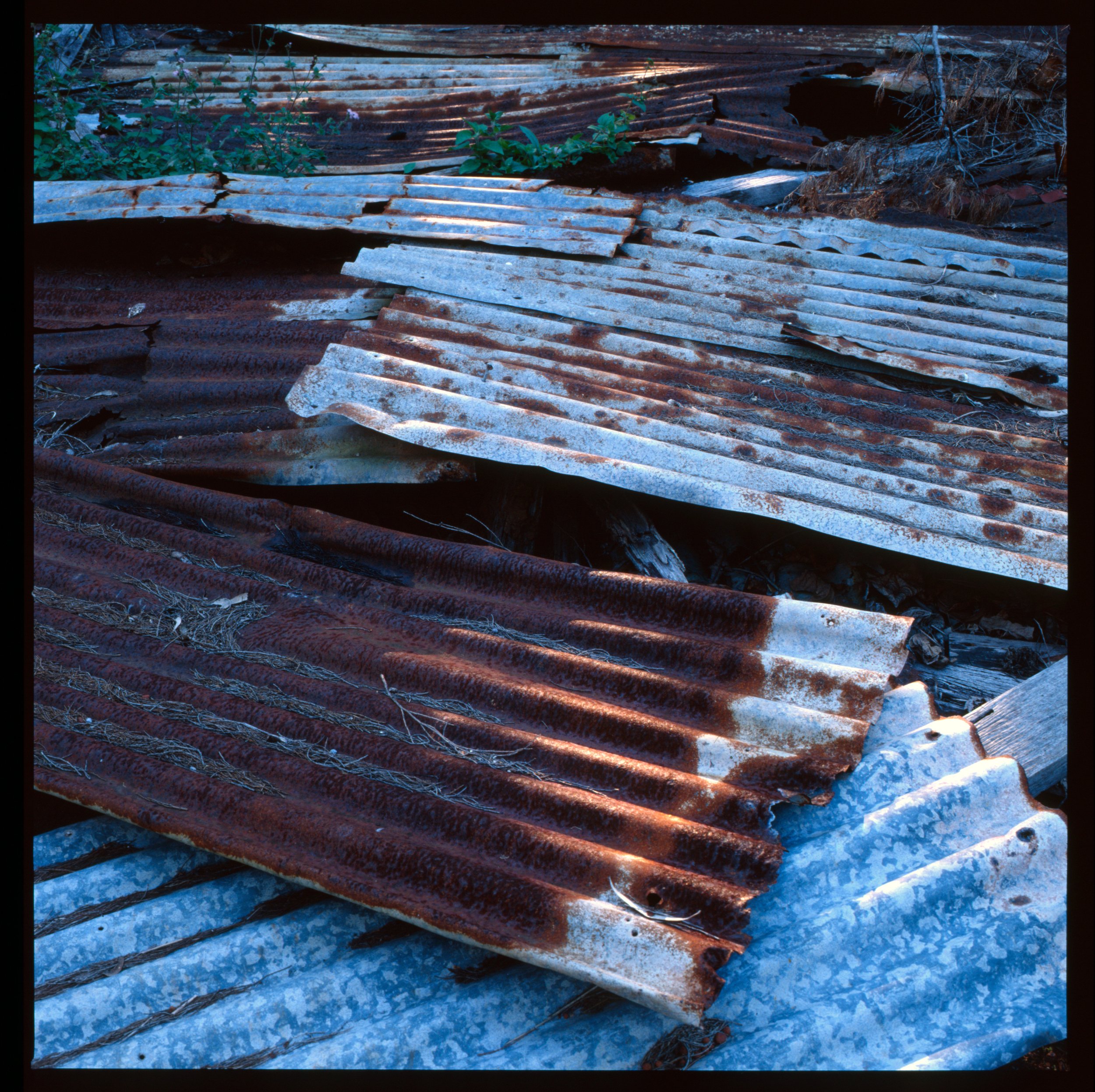

One of these is concrete. This is the subject of one of Moe’s images that has been taken from inside one of the huts reserved for indigenous inmates at floor level, revealing a concrete floor that lies broken up and destroyed. Tendrils of vegetation are pushing their way through the cracks, and the dark doorway frames the simple form of another indigenous hut beyond. Moe describes the long-term struggle that had to be undertaken before the indigenous inmates were given the rights to have concrete in their vestigial dwellings. He calls upon historical evidence that details the bare earth of the flooring of accommodation in which four inmates were expected to dwell at a time. This series also details the corrugated iron of which the huts were constructed, and the artist talks about how these materials bear evidence of power and struggle; the metal huts of the indigenous dwellings made for infinitely more severe experiences of weather than did the wooden buildings of the white patients and the workers.

Hut, UltraChrome on Ilford Smooth Pearl, 61x61 cm, 2008

Utensils, UltraChrome on Ilford Smooth Pearl, 61x61 cm, 2008

Many of Moe’s images focus on the deterioration of surfaces – the rust on enamel pots and implements, the highly textured bark of a tree, the pitting on metal implements, and the patina on an abandoned cicada shell. He speaks of the settlement as a place where everything is falling apart – the buildings, the implements, the history, the memories. He speaks also of the slow deterioration of the human body as the effects of Hansen’s Disease gradually took hold.

English is the third language in which Moe is proficient, and it is perhaps partly for this reason that he finds such interest in the ways in which things are described in the historical accounts of Peel Island. There is evidence enough of ironies in such language. He is interested in the fact that the historical literature refers to “the patients,” who seem in fact to be treated more like inmates. He is also interested in the battle for including “kitchenettes” in each of the women’s huts – a term that seems so feminised and dainty – the battle for which had been started by the infamous Rose Donovan who “was always misbehaving.” The success of this struggle meant that the women were able to – and from then on were expected to – eat on their own; in the end, perhaps a kind of Pyrrhic victory in a place where isolation was so profound. Moe’s interest in such contradictions is seen when his images are exhibited as series; the relationships between the individual works suggest the tension that exists between the will to exist and perform as an individual and the drive to be part of humanity as a whole.

— Pat Hoffie, Moe Louanjli in Resurrection on the Shorelines: A Short Speculation on the Role of Islands as Metaphors in the Twenty-first Century, Junctures #12, Dunedin, 2009.